George Floyd’s murder felt like everything was the same and nothing was the same, said Miski Noor, an activist in Minneapolis, where Floyd was killed by a white police officer a year ago on 25 May.

“How many times have we seen Black death go viral?” asked Noor, the co-founder of Black Visions, which advocates for abolition, an approach to public safety that does not involve the police.

Noor, who helped found the group in 2017, knows that to abolish policing you also must confront systemic racism and the weight of history. And Noor also knows as the child of Somali immigrants, that the issues are global.

The high-profile murder of Floyd, who was pinned under the knee of a police officer for nine minutes and 29 seconds, captured the parallels between police violence against Black people across the globe, and evoked the deaths of Adama Traoré in France and Mark Duggan in the UK before him, even though the circumstances of the deaths differ. And the execution reflected a common history of violence against Black people, from slavery to colonialism, that united protesters in a renewed global movement against the legacy of empire and its enduring racist symbols.

Since his death, those public images have rapidly come down – from the toppling of a statue honoring the slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol, England, to the official removal of the Confederate leader Jefferson Davis’s statue from the Kentucky state capitol.

More statues honoring the Confederacy, the band of southern states that fought against the US government in the civil war, have been taken down in the past year than in the previous four years, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). Since Floyd’s death, nearly 170 statues, street names and other tributes to the Confederacy have been removed or renamed in the US, SPLC data shows. More than 2,100 tributes to the Confederacy remain in public places; over 700 are monuments.

This reclaiming of public history isn’t new, but Floyd’s death was the latest catalyst, said historian Robin DG Kelley. “There has been a continuous reckoning around public history and race,” said Kelley, Gary B Nash endowed chair in UShistory at the University of California, Los Angeles. “And it wasn’t his death but the presence of 26 million [protesters] and the fear it generated that compelled institutions to act.”

Demands to remove monuments, change names and decolonize history were a part of the US culture wars of the 1990s, which included defending ethnic studies at universities. More recently, the Rhodes Must Fall campaign, the successful 2015 student movement in South Africa to remove a statue of Victorian imperialist Cecil Rhodes from the University of Cape Town, has inspired similar action in the UK and other countries.

Noor, who uses the pronoun “they”, said they were taught a whitewashed version of US history through the perspective of white, cisgendered men, while growing up in Rochester, Minnesota.

“To sell so many untruths, so many lies as factual, you have to actually erase. You have to omit whole lived histories,” said Noor, who delved deeply into African and African American history for the first time while attending the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities.

Historian Nell Irvin Painter, who addresses Confederate iconography in an ink, graphite and collage series called From Slavery to Freedom, said many people weren’t ready to reckon with the symbols until Floyd’s death.

“When the big public got ready around 2020, all this came to the fore,” said Painter, author of The History of White People. “[Floyd’s] murder was so egregious that you just couldn’t pretend it didn’t happen. Like with civil rights, there’s a long history that most people hadn’t known about … that could only be seen by lots of people at the right historical time.”

That was also true in the UK.

In what historians describe as an “unprecedented” public reckoning with the British empire, an estimated 39 names – including streets, buildings and schools – and 30 statues, plaques and other memorials have been or are undergoing changes or removal since last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests in the UK.

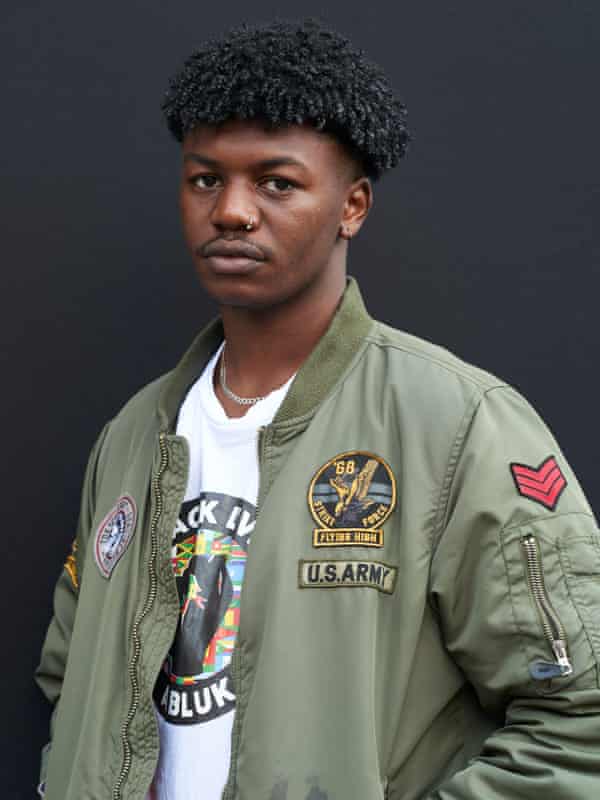

“The death of George Floyd sparked an exploration for me on how this country deals with racism. It was a big awakening,” said Tyrek Morris, a university student in Manchester.

Morris, who organized his first protest following Floyd’s death, said wherever he turned, he saw placards with an enduring slogan: “The UK is not innocent.”

The message reverberated deeply within him and started him on a journey where he interrogated what he was taught and, more importantly, what he wasn’t. At these Black Lives Matter protests, Morris heard from the family of Mark Duggan, whose death at the hands of the police sparked the 2011 London riots; of Shukri Abdi and Christopher Kapessa, two children who drowned, but whose families say authorities failed to take their cases seriously; of the crimes of the British empire and a frank assessment of Britain’s role in the slave trade.

An estimated 15,000 people marched with Morris, who organised with the group All Black Lives UK (ABLUK), in Manchester on 6 June, one of 160 protests that weekend. ABLUK also organized a gathering of 10,000 demonstrators in Bristol, where they toppled a statue of the 17th-century slave trader Colston. Xahra Saleem, a writer who runs a small jewellery business, clearly remembers the moment the Colston statue was taken down. She was one of the organisers of the protest and was walking ahead of the march. She passed the statue and joked to a friend: “Wouldn’t it be crazy if it fell down at some point?” Then it did. “It was like we manifested it,” she said.

A decades-long campaign by the local community to get the statue removed had been ignored by the local authority. But once the statue fell, everything changed.

“Schools changed their names and roads’ names changed. Everything happened so quickly. Sometimes all it takes is a little bit of a push,” Saleem said.

In France, the only country that outlawed slavery and later reinstated it, outrage over Floyd’s death quickly revived a tense debate about the weight of colonial history and the country’s slave-trading past. Starting in French Caribbean islands, statues were pulled down or defaced by protesters. In Martinique, a long-simmering controversy over white figures on plinths boiled over: statues of the white politician Victor Schœlcher, who facilitated the decree to abolish slavery, were targeted amid calls for more visibility for the rebellions by enslaved people, which led to abolition.

“George Floyd’s death opened up a lot of debate on race in France – around questions of white privilege, police violence and racism in the police as well as France’s colonial past,” said Rokhaya Diallo, a writer, broadcaster and anti-racism campaigner.

“But there was also a lot of resistance and denial of the problem, particularly in TV studio debates,” Diallo said. “There will always be some denial, but what has changed is that we can no longer ignore the issue. The lid can’t be put back on, particularly for young people today.”

France was the first country to officially recognise slavery as a “crime against humanity” – enshrined in a 2001 law which set out to improve the teaching of slavery and the colonial era. But historians have raised concerns that teaching in French schools is still too little.

“The Napoleon commemorations in France this May showed that this is still a debate,” Diallo said of the bicentennial observance of the emperor’s death.

Though he has promised to be “uncompromising in the face of racism, antisemitism and discrimination”, President Emmanuel Macron has insisted that France would not take down statues of controversial, colonial-era figures.

The response to Floyd’s death “already had an international dimension”, historian Kelley said. “It wasn’t simply sympathy for another African American victim. It was recognition that this kind of violence was happening all over the world.”

Floyd’s case was eerily like that of Adama Traoré, a 24-year-old Black man, who died after being stopped by gendarmes outside Paris in 2016. Pinned to the ground, he told officers: “I can’t breathe,” just as Floyd did. Investigating judges are examining conflicting medical reports in his case.

Assa Traoré said her brother initially ran from police because he didn’t have his identity card with him, an extension of life there. A Black or North African man in France is 20 times more likely to be stopped for an identity check than a white man, research shows. And those controls can end in violence or death.

Black people enslaved by he French had to carry official documents, according to Traoré, who said the need for documentation “links back to everything that is unsaid about colonial history and its consequences … As long as the French police doesn’t confront its past and say there is racism in the police, we won’t get anywhere, it’s a struggle that will never end.

“So yes,” Traoré said, “statues and street names are a start in a country facing up to the violence of its past.”

For Bree Newsome Bass, who in 2015 removed the Confederate flag flying at the South Carolina statehouse, the whole story of America is in question, similar to the debates in France and the UK.

“We tend to think of ourselves as having broken free of colonialism, but what is lost is the history of genocide of the indigenous Americans. I’ve really come into recognizing what that means in terms of how we think of America, as this new nation as opposed to what it is, which is really a colony,” said Newsome Bass, a film-maker and activist. “It began as a slave colony, and even though we broke off from Britain, the United States evolved into its own white settler colonial state.”

Since Floyd’s death, there is a new roll call of Black people in the US who have died at the hands of police, a painful reminder of what hasn’t changed when the statues came down. While Derek Chauvin was convicted of killing Floyd, names like Rayshard Brooks and Daunte Wright join a growing list of lives lost, linked to steady demands for institutional change and greater accountability.

Kelley said events of the past year illustrate how easy it is to topple a statue or change the name of a building, and how difficult it is to topple an empire, dismantle racial capitalism and patriarchy, and replace prisons and jails with “non-carceral, caring forms for public safety”.

The situation also creates a quandary, Kelley said. What do we make of universities that change building names but have huge real estate holdings in neighboring low-income communities or endowments with investments in private prisons or occupied Palestine? What do we make of Barclays Bank removing the name of enslaver Andrew Buchanan from its new Glasgow property, and yet it has its own sordid history with trading the enslaved?

“[Removing symbols] makes us feel good, but it ironically has the effect of personalising and individualising racism,” Kelley said. “Some of the most important British abolitionists, for example, came from the ranks of industrial capitalists. Do they stay or fall?”

In the UK, campaigners also fear that changes such as removing statues are cosmetic. Robert Beckford, a professor of Black theology at the Queen’s Foundation, said: “Presenting a more balanced view of the history is necessary, but I’m worried that removing the symbols, removing of a plaque is viewed as equivalent to anti-racist, institutional change.”

For Morris, the work has only just begun. He points to the British government’s controversial report on race, which claimed to not find evidence of institutional racism in the UK in the areas it studied, as a sign of how far the UK must go to confront its past and present. He believes the answer to that is more protests.

Saleem, who organised the Colston protest, agrees. “We’re planning to make it a summer of anti-racist movements, activities and protests.”

The work continues in Minneapolis, too. This summer, Black Visions plans to gather residents to answer the question: “What will keep us safe?” The goal is to have a mandate and collective definition of safety that is driven by Minneapolis residents and includes alternatives to current approaches to public safety.

A coalition called Yes 4 Minneapolis submitted a petition to change the city charter, which requires the city to rely on police for public safety. The petition calls for a November ballot question to allow residents to replace police with a public safety department.

“I want to see more of my people and my ancestors reflected in the world that I live in,” said Noor. “But how about we just build that world instead of just changing the street signs in this one?

“It’s Black folks continuing to fight for the basic right … to live so we can thrive. George Floyd is a part of that story.”

Comments