LONDON – When Theresa May became prime minister, she had grand designs. Her premiership wouldn’t just be about taking Britain out of the European Union, it would be about fighting “the burning injustice” within the country.

But on Wednesday night, broken by Brexit like her predecessor, May effectively conceded that she won’t be able to do anything more to battle injustice, empower women, and build a more equal society.

May told lawmakers from her Conservative Party that she will move out of 10 Downing Street as soon as Brexit is delivered, leaving the messy business of building a future relationship with Europe to another leader. That paves the way for what will likely be a fierce succession battle in the Conservative Party.

It is a sour moment for May, who for nearly three years has ploughed an often solitary path to get a Brexit agreement with the EU. Following two hefty defeats for her deal, she’s offered her premiership in return for getting the necessary support for her plan.

What she had anticipated as a moment of triumph — actually delivering Brexit — has morphed into some kind of humiliation.

Like David Cameron before her, she will leave Downing Street earlier than planned, a victim of the same deep divisions in her party over Europe.

Hers has been a hapless task. She campaigned to keep Britain inside the EU in the 2016 referendum — albeit quietly — and then took over from Cameron with the mandate to take Britain out.

May set her course early on in the Brexit negotiations when she decided not to seek cross-party cooperation for the type of Brexit she would pursue. She instead spelled out a series of “red lines” that she vowed never to cross that narrowed her options in the tough negotiations with the EU over the divorce.

She decided Britain would leave the European single market, come out of the customs union with Europe, and sever many economic ties that have increasingly bound Britain to continental Europe for decades.

Her single-minded pursuit of these goals did eventually lead to a complex agreement, but when the details were made public, many in Parliament — and many of the most prominent Brexiteers in her own party — rebelled. She was soon stung by a series of high-profile resignations, including her foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, and her Brexit secretary, David Davis.

The pro-Brexit wing of the party said the plan would leave Britain subject to EU rules after it leaves. Pro-EU Conservatives criticized May for ruling out a so-called softer Brexit in which Britain remains in the EU’s single market and customs union, perhaps averting a Brexit-fueled economic contraction which the Bank of England has warned could see the British economy shrinking 8 percent in a matter of months.

As the months of negotiations dragged on, she effectively lost the “hard Brexit” faction in her own party, without presenting a “soft Brexit” that would satisfy the Labour Party voters she would need to get the plan approved by Parliament.

The result: stagnation, humiliation, and an early exit.

It’s been a jarring end after a promising start. When May came to power in July, 2016, she came through the middle after more prominent figures, including Johnson and then Justice Secretary Michael Gove, fell out acrimoniously.

Any idea that she had a political Midas touch evaporated quickly when she made a fateful decision to call a general election for June, 2017, three years before one was required.

It is revealing that she seemed to make this momentous choice on her own, without much input from her staff, while rambling in the Wales countryside with her husband, Philip, during a break from her duties.

The result was calamitous. May fared so poorly during the campaign that her party lost its majority in Parliament, gravely weakening her authority, and leading directly to the predicament she faces today, when she can only get her plan approved if she gets at least some support from other parties.

A more flexible politician might have decided at that time that a minority position in Parliament would require reaching out to others for something as divisive as a Brexit deal, but May opted to go it alone.

May, 62, is a steely, determined politician who admitted Wednesday night that she doesn’t do well in bars or with gossip. Her approach to setback has been to push back and push on, repeating the same talking points — “Brexit means Brexit”, for example — almost to the point of self-parody..

Few doubt her fortitude and commitment to an idea of public service instilled in her upbringing as the daughter of an Anglican vicar. Her career has not been tainted by tales of personal greed or corruption, and she has earned praise for soldiering on in an extremely demanding position despite suffering from type 1 diabetes.

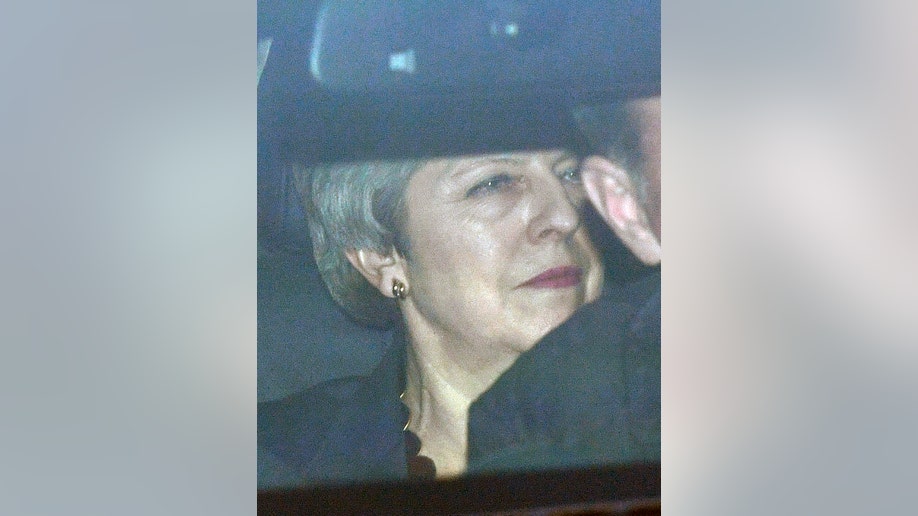

It was by all accounts an emotional moment when she told fellow party members Wednesday night she would step down early, despite her clear, stated preference to remain in office.

George Freeman, a former adviser, said she had “tears not far from her eyes” as she admitted she had fallen short.

He said May admitted making “many mistakes” and said she was “only human.” Freeman said that behind closed doors May said, “I beg you, colleagues, vote for the withdrawal agreement and I will go.”

The crowded room fell silent at that point.

“She is falling on her sword, putting country before party and career, and is asking them to do the same. You could hear a pin drop in that room,” Freeman said.

___

Follow AP’s full coverage of Brexit at: https://www.apnews.com/Brexit

Comments