From flood to fire, 2021 has been a summer of extraordinary extremes across the globe — a sign that the impacts of climate change are already widespread and accelerating. Such extremes, and their connection to human-caused climate change, are just one main theme in a landmark climate report released Monday by the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Written by more than 230 leading scientists from countries around the world, it is part of the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report — the most significant climate report published in years by the international science community.

The report is a synthesis of work from over 14,000 research citations. It is, in effect, a climate science encyclopedia — a summary of the latest scientific consensus on climate change and what the future portends, through the use of sophisticated climate models and knowledge of past conditions. It is an update on how the Earth’s climate and our understanding of it have changed since the last such report in 2013.

“It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land,” the report states. Many of the changes inflicted on the planet — especially our oceans — will be “irreversible for centuries to millennia,” and continued warming will lead to an acceleration of “extreme events unprecedented in the observational record,” it warns.

U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres called the report a “code red for humanity.” Guterres said, “the alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable: greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel burning and deforestation are choking our planet and putting billions of people at immediate risk,” CBS News’ Pamela Falk reports.

But also conveyed in the report is the knowledge that there’s still time to take action on the climate crisis. The report makes clear that every increment of temperature rise matters, so less warming will help lessen disaster. That will require steps like rapidly reducing methane emissions in the short term and greenhouse gases overall. The science shows that if society is able to follow a low-carbon path into the future, it will “yield rapid and sustained effects to limit human-caused climate change,” the report says.

One of the report’s lead authors, Professor Ed Hawkins, from the University of Reading in the U.K., says the main messages he hopes readers will take away from the report are that “climate change is indisputably caused by human activities (primarily fossil fuel burning and deforestation), and that this is already affecting every region, including making extreme weather events worse.”

“Immediate, rapid and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are required to limit global temperature rise,” he said.

Unprecedented changes

Scientists have known since the 1800s that gases like carbon dioxide warm the planet by trapping heat. By the 1960s it was clear to scientists, and even Big Oil companies, that increasing atmospheric greenhouse gases through the burning of fossil fuels carried with it harmful consequences for the planet.

As the telltale signs of climate change became more apparent, the international community agreed to come together to address the issue. In 1988, the IPCC was formed by the World Meteorological Organization and the UN Environmental Program. As an intergovernmental body, it is comprised of scientists and political representatives tasked with providing the world with objective science on climate change and outlining the risks, consequences and possible responses. The IPCC has produced comprehensive assessment reports every few years beginning in 1990, with other special reports in between.

Like the 2013 assessment, this year’s report leaves no wiggle room for skeptics, stating that it is “unequivocal” that human actions have warmed the planet. “Widespread and rapid changes” have already occurred, and the impact is increasingly being felt around the world.

“Large-scale indicators of climate change in the atmosphere, ocean, and cryosphere [frozen areas] are reaching levels, and changing at rates unseen in centuries to many thousands of years” due to human-caused warming, the authors say.

Some of the key findings include:

- C02 levels

Levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations in the atmosphere are higher today than at any time in the last 2 million years. For methane it’s at least 800,000 years. And the rate of increase of greenhouse gases exceeds all natural changes during that same time period.

- Rising temperatures

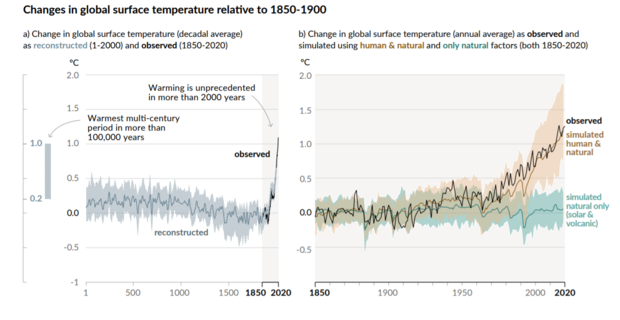

As a result, temperatures over the last 50 years have increased at a rate faster than any time over the last 2,000 years. Average global surface temperature was 1.1° Celsius (2 degrees Fahrenheit) higher in 2011–2020 than in the period from 1850–1900 (before human industry started warming the planet), with stronger warming over land (1.6°C) than over the ocean (0.9°C). It is likely that the most recent decade is as warm as any period since the last interlude between Ice Ages — 125,000 years ago.

IPCC

- Ice melt

Warming temperatures are melting ice at unprecedented rates for modern times. Late summer Arctic sea ice coverage is less than any time in the last 1,000 years. Glacier retreat is unprecedented in the last 2,000 years, with almost all of the world’s glaciers retreating synchronously since the 1950s.

- Sea level rise

Greenhouse gases, warming and ice melt from land are leading to huge change in the oceans. The rate of sea level rise is the highest it has been in at least 3,000 years. Global mean sea level increased by about 8 inches between 1901 and 2018. And the pace is accelerating: The rate of increase was 1.3 mm per year between 1901 and 1971, but increased to 3.7 mm per year between 2006 and 2018.

Some 90% of the excess heat trapped in the Earth system is stored in our oceans. As a result, the ocean is gaining heat faster than at any time since the end of the last Ice Age.

- Ocean acidification

Carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater and makes the ocean more acidic, which poses a threat to coral and other sea life. Ocean acidification is now at levels that are “unusual in the past 2 million years,” the report says.

Climate change and extreme weather

Discussion of extreme weather is a big part of this year’s report, which states, “Human-induced climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe.”

The warming climate is driving more heat waves, heavy precipitation, increases in the most intense hurricanes, droughts and compound events, where the impact of multiple disasters pile on top of each other.

And the report warns there is worse to come. With 1.5°C of global warming — a level we will likely hit in the 2030s — it says we should expect to see “extreme events unprecedented in the observational record.”

- Heat waves

Heat waves have the most obvious connection to global warming. They have become “more frequent and more intense across most land areas since the 1950s,” the report says. Recent extremes would have been “extremely unlikely to occur without human influence on the climate system.” It also notes that marine heat waves — unusually high temperatures in ocean waters — have nearly doubled since the 1980s, with human fingerprints on most of them.

- Precipitation

As air temperatures increase, the atmosphere can hold more moisture and thus produce heavier rainfall. As a result, heavy precipitation events have increased in both frequency and intensity since 1950.

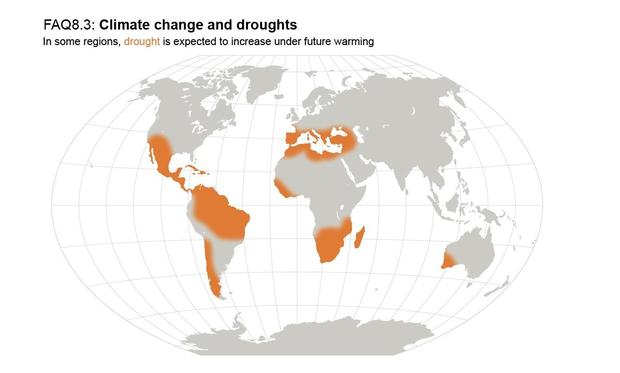

- Drought

Climate change is contributing to droughts as well, often because of warming leading to increased evaporation from soils and vegetation.

- Tropical cyclones

With warmer ocean temperatures and more atmospheric moisture available, tropical cyclones and hurricanes are undergoing changes. The global proportion of major storms (Category 3–5) has increased over the last four decades, and climate change also increases the heavy precipitation associated with them.

Future climate scenarios: How much warmer?

For each IPCC assessment cycle, a suite of climate models are run to help project our changing climate into the future. As the years have progressed, these models have become more sophisticated and higher resolution. The effort is called the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) made up of around 100 climate models from 50 different international modeling groups.

One big advance made for this year’s report is the narrowing of the range of warming projected from the doubling atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations in the atmosphere — a concept called the Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity (ECS). In the previous report, the ECS ranged between 1.5°C and 4.5°C — a very large uncertainty which would yield completely different climate outcomes.

Now, through analysis of improved model output, scientists were able to reduce the ECS uncertainty to a best estimate of 3°C of warming, with a likely range of 2.5°C to 4°C.

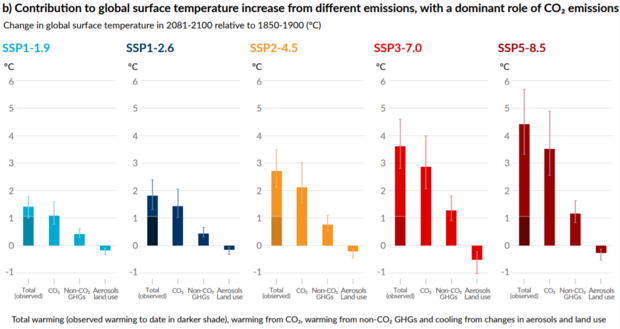

For this report cycle, the modelers ran a set of five emissions scenarios to explore how the climate is likely to respond to various levels of greenhouse gasses, differences in land use and air pollution. The models also account for the potential impact of solar activity and volcanoes. These scenarios are meant to offer a window into how our choices help shape the planet’s future.

Although the IPCC does not weigh in on the plausibility of any one scenario, it’s generally understood that the lowest and highest emissions scenarios are unlikely and act as a lower and upper bound on possible climate futures. It all hinges on what humanity does, or does not do, to combat climate change.

Based on these models, the report concludes that global surface temperature will continue to increase until at least the middle of this century under all emissions scenarios. Global warming targets of no more than 1.5°C or 2°C above the pre-industrial average — the goal of the Paris Agreement — will be exceeded during the 21st century unless there are “deep reductions in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions in the coming decades.”

There is a wide range in possible warming (seen in the chart below) depending on which scenario comes closest to reality. In a scenario where CO2 emissions are dramatically and swiftly reduced, warming may stay near the goal of 1.5°C. But for a very high emissions scenario, warming as high as a catastrophic 5.7°C is possible.

Experts agree that both of those scenarios are very unlikely. The more likely outcome is an intermediate scenario of closer to 3°C of warming.

IPCC

In any case, global warming of 1.5°C, relative to 1850-1900 levels, is likely to be met or exceeded in all five scenarios and that is likely to happen before 2040. In the highest emissions scenarios, temperatures blow right past the 1.5°C goal. But in the lowest emissions scenario there is only a temporary overshoot of the goal.

In regards to the 2°C warming threshold, the three higher emissions scenarios all result in breaching that upper-end target. The two lowest emissions scenarios are very likely to limit warming below 2°C.

These different scenarios make it clear that humanity has the power to limit the worst impacts of climate change if we collectively choose to.

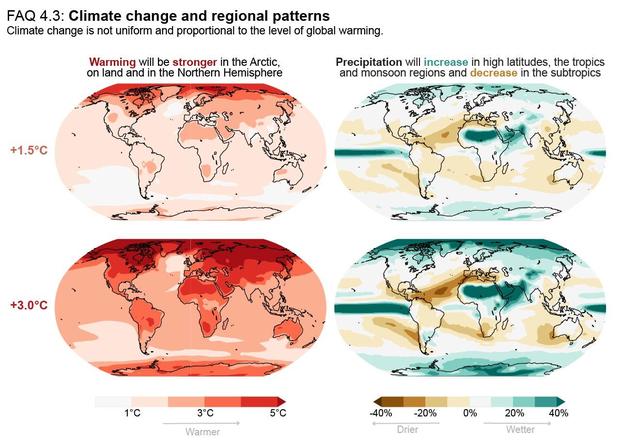

Uneven impacts: Hotter, wetter, drier

In the maps below you can see how different regions of the Earth are projected to warm under different levels of global warming. The Arctic, which is already warming at three times the average rate, will continue to lead the way. And land areas — where people live — will continue to warm faster than the ocean, with regions affected in different ways.

IPCC

Overall the Earth will get wetter, but some areas will experience greater dryness. These wet and dry trends have generally been consistent through decades of climate modeling. This is due to an intensification of the water cycle and prevailing weather patterns. It’s clear that high latitudes and monsoon areas of Africa and India will get wetter, meaning flooding in areas less prepared for these extremes.

Meanwhile, areas vulnerable to water stress and fire will continue to plunge deeper into drought. These areas include the Southwest U.S., Central America, the Amazon, southern Africa, the Mediterranean and Middle East. All of these areas have faced both water shortages and out of control wildfires and that trend will continue.

IPCC

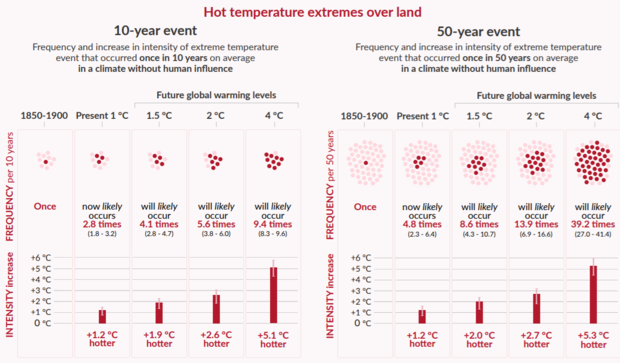

One thing that has become abundantly clear the past few years is that as temperatures rise, extreme conditions become more likely, in some cases at an accelerating rate. This is especially true for hot weather extremes. Both the frequency and intensity of heat waves will continue to noticeably increase, even with seemingly modest increases in global warming.

Extreme heat events like the kind that a region would expect to experience once every 50 years in the world before climate change have already increased by about 5 times. These types of deadly conditions will multiply as warming continues.

IPCC

Rainfall also has a direct connection to how warm the atmosphere is, and the report indicates that heavy precipitation events will continue to increase in both intensity and frequency. In the Northeast U.S., heavy rain events have already increased by roughly 50%.

Because a warmer climate intensifies the water cycle, it’s not just heavy precipitation events that will increase; drought will as well. Though average precipitation will increase in most places, more will fall in heavy events, not moderate rainfall spread out over time.

The bigger impact on drought occurs because more heat energy in the system means enhanced evaporation, drying out vegetation and soils. We see the result of that across the West, where since 2000 a naturally dry long-term pattern has teamed up with climate change to fuel the worst two decades of drought in over a millennium.

With greater warming, heavy precipitation and drought events that would only be expected once every 10 years in a given region will also happen more frequently. There is a steady increase as temperatures warm, but it is worth noting that the heaviest precipitation events, like the devastating floods in Western Europe this summer, will increase at an even faster rate, overwhelming existing infrastructure.

As we now approach the peak of hurricane season, and given the monster storms of the past few hurricane seasons, the report’s warning about storm trends is also concerning.

“The proportion of intense tropical cyclones (categories 4-5) and peak wind speeds of the most intense tropical cyclones are projected to increase at the global scale with increasing global warming,” it says, though it notes the science is still not clear on whether the number of tropical systems will increase or decrease.

In the colder regions, additional warming will obviously mean amplified permafrost thawing and loss of seasonal snow cover, land ice and sea ice. Under all of the emissions scenarios, the Arctic is likely to be practically free of sea ice in September (when it reaches its annual minimum) at least once before 2050.

Compounding the impact of ice melt is the fact that ice reflects the sun’s rays back into space and helps keep warmer air and water from reaching the Arctic, so the loss of ice acts as a self-reinforcing feedback loop, accelerating warming. Thawing permafrost releases long-trapped greenhouse gases, another feedback which will increase.

Impact on oceans will last for centuries

While limiting warming will be necessary to preserve Earth’s ability to support life in the future, there are certain changes already baked into the system which are irreversible on century time scales. Even if we were to stop warming today, the seas will keep rising and the ice will keep melting because the ocean stores, circulates and releases heat over much longer periods.

“Sea level is committed to rise for centuries to millennia due to continuing deep ocean warming and ice sheet melt, and will remain elevated for thousands of years,” the report says.

For instance, we know from the science of paleoclimatology, which uses evidence in the fossil record like ice cores, tree rings and ocean sediments, that 125,000 years ago, in between Ice Ages, sea levels were much higher than today — but temperatures were roughly the same as today. This leads to the conclusion that, through continued ice melt, seas will continue to rise for hundreds of years, eventually reaching levels last seen during that time period.

Under the intermediate emissions scenario considered in the report, global sea level is projected to rise by up to 2.5 feet by 2100 and over 4 feet by 2150. That’s without factoring in any potential collapse of ice sheets in Greenland or Antarctica, which with more warming becomes more probable.

Over the next 2,000 years, the report projects that global mean sea level will rise up to 10 feet if warming is limited to 1.5°C, or up to 20 feet if warming tops out at 2°C.

But it gets even worse if we warm past the Paris Agreement climate targets. Then our comparable climate is millions of years ago, when sea levels may have been more than 70 feet higher than today.

Darrell S. Kaufman, a paleoclimatologist at Northern Arizona University who studies past climate stretching back millions of years, told CBS News, “As a paleoclimate scientist, I see lots of evidence that climate can change dramatically when it’s pushed. Humans are pushing the climate. There’s no going back, but we could limit the worst effects if we make major rapid reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.”

Perhaps the most worrying aspect of the report comes in its look at so-called low-likelihood but high-impact events, such as ice sheet collapse or an abrupt alteration in ocean circulation. Although the probability or timing of these can not be forecast with any degree of accuracy, the report says such occurrences cannot be ruled out and must be part of our risk assessment.

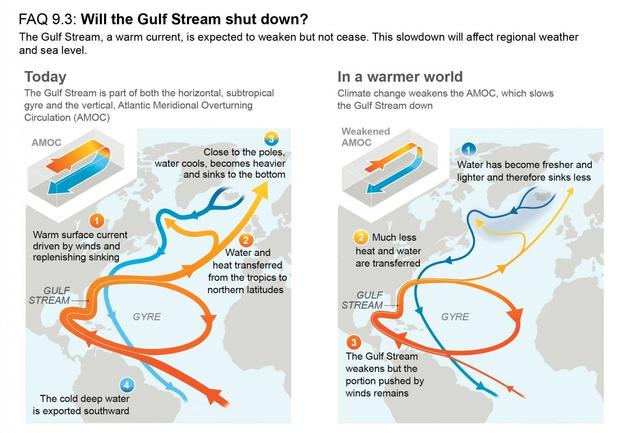

One example of such an event is a potential tipping point in the Atlantic Ocean current system known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, which has been weakening or possibly even heading for collapse. The system, which circulates warmer waters northward from the tropics and sends cooler water south in deeper currents, has far-reaching effects on weather patterns across large portions of the globe.

IPCC

The concern over this has been growing. Just a few years ago the IPCC felt that a collapse in this very important ocean circulation was not likely for hundreds of years, but now they are not so sure. Now the authors say the AMOC is “very likely to weaken over the 21st century for all emission scenarios,” and they are only able to say that “there is medium confidence that there will not be an abrupt collapse before 2100.”

If such a collapse were to occur, it would very likely cause drastic shifts in regional weather patterns and the water cycle, causing widespread and significant impacts on rainfall and drought.

“It’s a solvable problem” — but there’s no time to waste

The portion of the report called the Summary for Policy Makers was finalized last week in a marathon session in which delegates from 195 member countries weighed in and agreed upon the final language.

“The government delegations discuss the wording of every single sentence in extraordinary detail,” Hawkins explained. “There is often some compromise between the different delegations on the precise choice of words — it is their summary for policymakers, so needs to include the information that is relevant for the governments — but the scientists always have the final word. If the wording is not consistent with the underlying scientific assessment then the discussions continue until it is consistent.”

While some of the final wording may not be as bold as many in the science community would have liked, Hawkins notes, “The language is pretty stark for an IPCC report.”

Andrew Dessler, a climate professor at Texas A&M University, told CBS News that there’s a good reason countries have to unanimously agree on every sentence of the Summary for Policy Makers.

“These documents serve as the starting point for climate negotiations,” explains Dessler. “Given the process the SPM goes through, no country can later say they don’t agree with the science. They’ve already agreed to it.”

While there’s a lot of doom and gloom in our climate reality, the report makes clear that we still have a limited amount of time to avert the worst outcomes.

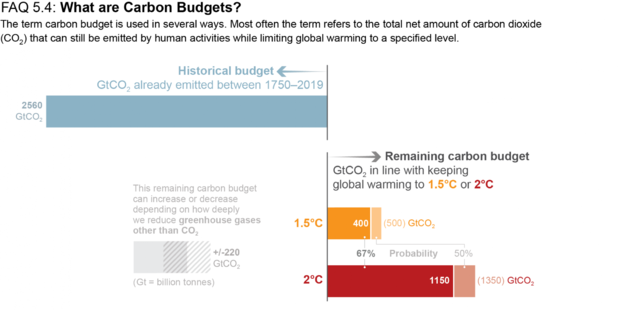

To do so “requires limiting cumulative CO2 emissions, reaching at least net zero CO2 emissions, along with strong reductions in other greenhouse gas emissions,” the authors write.

The greenhouse gas which can make the biggest impact in the short term is methane, which has about 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over the first 20 years. Methane has been rising rapidly in recent years due to emissions from natural gas and livestock. So the report specifically calls for “[s]trong, rapid and sustained reductions in CH4 [methane] emissions.”

The chart below helps put the scale of the task in perspective. Since we first started burning fossil fuels, humanity has emitted around 2,600 gigatons of carbon. To keep warming below 1.5°C, we can only emit another 400 gigatons, which on the present course we will do in 9 years or less. It’s a near impossible task. To avoid 2°C of warming, we have another 1,150 gigatons left — approximately 26 years at current rates. Most experts agree that is doable, but will require collective willpower and hard work.

IPCC

Breaching either one of these Paris Agreement targets will not result in falling off a climate cliff, but as warming continues, the impacts will increasingly overwhelm the planet’s human life-support systems — especially as they happen concurrently. So every increment of a degree matters.

The report says that taking the low emissions scenario, as opposed to the high emissions scenario, would result in a “discernible difference” in temperature trends in about 20 years. Scenarios with low emissions “would have rapid and sustained effects to limit human-caused climate change.”

Some reassuring news reaffirmed in this report is that warming increases in a linear fashion with increases in greenhouse gases. This means if we stop pumping carbon emissions into the atmosphere, Earth’s temperature will also stop warming very quickly.

Yet despite decades of warnings, emissions and warming continue at breakneck pace.

“It’s like we’re on a speeding train barreling towards a brick wall. It matters if we hit that wall at 200 miles per hour or if we hit that wall at 20 miles an hour,” says Kendra Pierre-Louis, a climate journalist working on the climate solutions podcast “How to Save a Planet.” Pierre-Louis believes that while national politicians bear a lot of the responsibility for climate action, each person can work at the local level to make change.

“Perfect is the enemy of good. The best climate issue to tackle is the one you can tackle provided you link it to systemic changes,” she said, offering as an example: “It is good to ride a bicycle. You can feel virtuous. But it’s better to push for the infrastructure to get say half your town out of cars, and onto a bike or walking or on transit.”

CBS News asked Pierre-Louis what message she hopes people will take from the IPCC report. She replied, “I want people to understand that it’s a solvable problem.”

U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres sounded a similar note in his call for action: “If we combine forces now, we can avert climate catastrophe. But, as today’s report makes clear, there is no time for delay and no room for excuses.”

Source Article from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/climate-change-impact-warning-report-united-nations-intergovernmental-panel-ipcc-code-red-humanity/

Comments